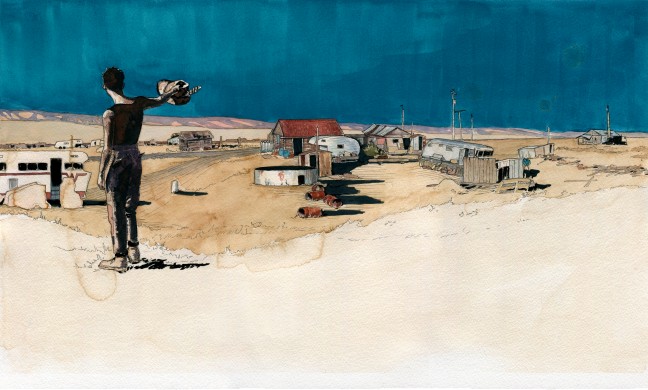

The peninsula northwest of the industrial city of Antofagasta, on Chile’s northern desert coast, is haloed with seabirds in flight. Pelicans lumber past wheeling gulls. Flocks of boobies cut the haze around Punta Tetas—Tits Point—like an avian punch line.

Farther from shore, where the inappropriately named Pacific begins its wild pitch and yaw, is the domain of the order Procellariiformes: birds with long, hooked bills and tubular nostrils that spend most of their lives above the open ocean. The largest of these are the albatrosses, soarers with severe brows and stiff, straight wings that span several feet. The smallest—small enough to hold in one hand—are the storm petrels. Most of the storm petrels that ply the air off this coast are brownish black, with crescents of lighter feathers across their shoulders and the erratic flight patterns of a bat. When they drop to the water’s surface to dip mouthfuls of food, they seem to run across it. This habit inspired the name of the birds’ original taxonomic family, recently split into two: Hydrobatidae, meaning “water walkers.”

The Spanish name for storm petrels is golondrinas de mar, or golondrinas de la tempestad—“swallows of sea,” “swallows of storm.” Sailors of old thought they heralded bad weather, and called them “Mother Carey’s chickens,” emissaries carrying warnings from the Virgin Mary or ship-sinking gales from darker spirits.

Among these far-flying little birds, one can be particularly difficult to find: the ringed storm petrel, or Oceanodroma hornbyi. It has dark wings with white half-moons, like the other petrels here, but its face and belly flicker bright white, and it sports a collar and a rakish masked cap of dark gray. While the other storm petrels seem abundant, the ringed arrives alone, and is gone quickly: a dipping turn like a wink, then away. It rarely appears less than 30 miles from shore, and ranges 300 miles farther out, where gossamer flying fish launch from wave faces like butterflies and the seafloor plunges thousands of feet.

To a storm petrel, the U.S. naturalist and author Louis J. Halle once wrote, the continents are a “mere rim for the once great ocean that envelops the globe.” This ocean is its own landscape, divided by changes in temperature, salinity, wind, and other factors into different habitats. Ringed petrels find theirs in the cold, nutrient-rich Humboldt Current that flows north from the southern tip of South America along the Chilean and Peruvian coasts. They spend so much of their lives over the Humboldt that they’re considered endemic to the current: more native to moving water than to earth.

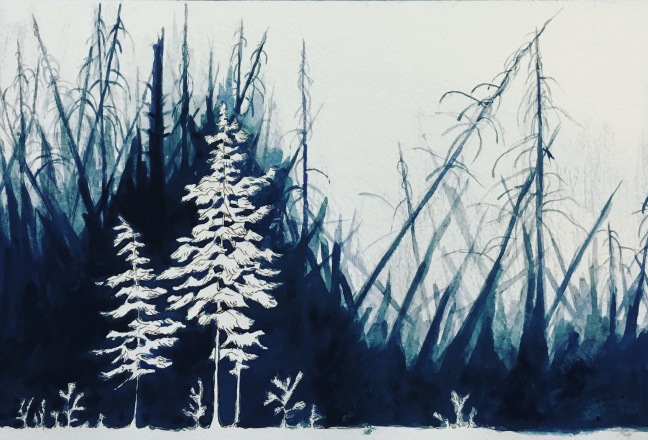

Even so, the birds must eventually alight on solid ground to raise their young, and on land they’re even harder to find. Like most seabirds, storm petrels often nest in extreme terrains, such as remote islands and seaside cliffs, which protect brooding adults, eggs, and chicks from mammalian predators. They tend to travel overland only at night, and hide in crevices by day.

For more than 150 years, the ringed storm petrel’s breeding grounds remained a mystery. Then, in April of 2017, a group of volunteer naturalists found the world’s first documented nests. They were 45 miles inland from the Chilean coast, deep in the driest nonpolar region on Earth: the Atacama Desert. More…

This article and my original illustrations appeared in

This article and my original illustrations appeared in

This article originally appeared in

This article originally appeared in