This essay originally appeared at The Last Word on Nothing on Jan. 28, 2019

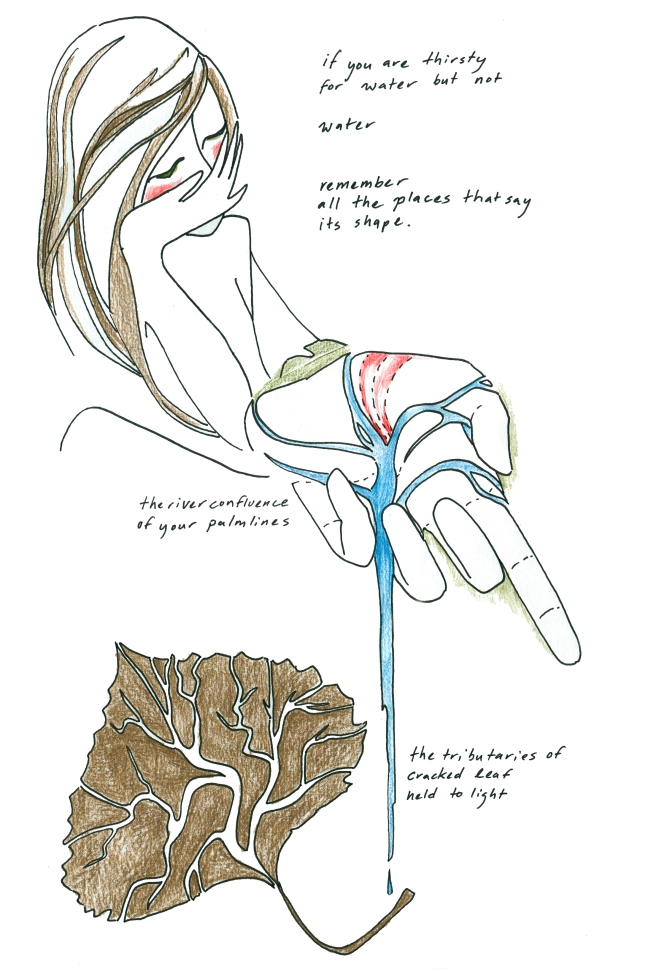

Fog is like water, in the valley where I live.

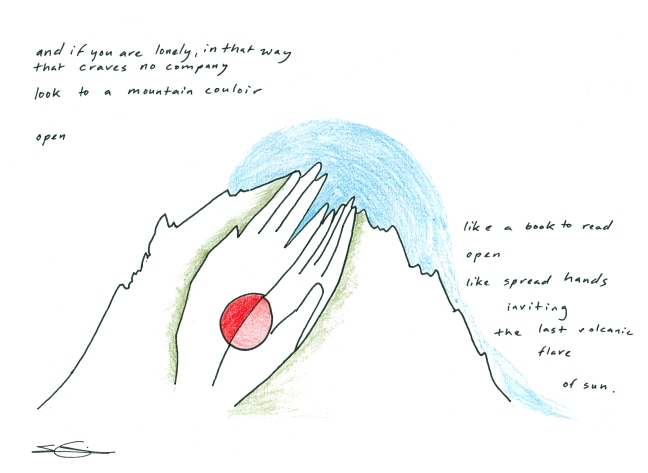

As dusk approaches, rivulets of cold air flow down the slopes and gullies of the surrounding mountains. They pool in the flats, the horizon line where dark brush rises from snow blurring as if smudged, the softness blending up, beginning to erase the world. Leaves and twigs vanish, then treetops. Layers like organza drift in one atop the other, settling toward the ground, light sighs of cloud. They sink the riverbed into sleep. They call other things awake.

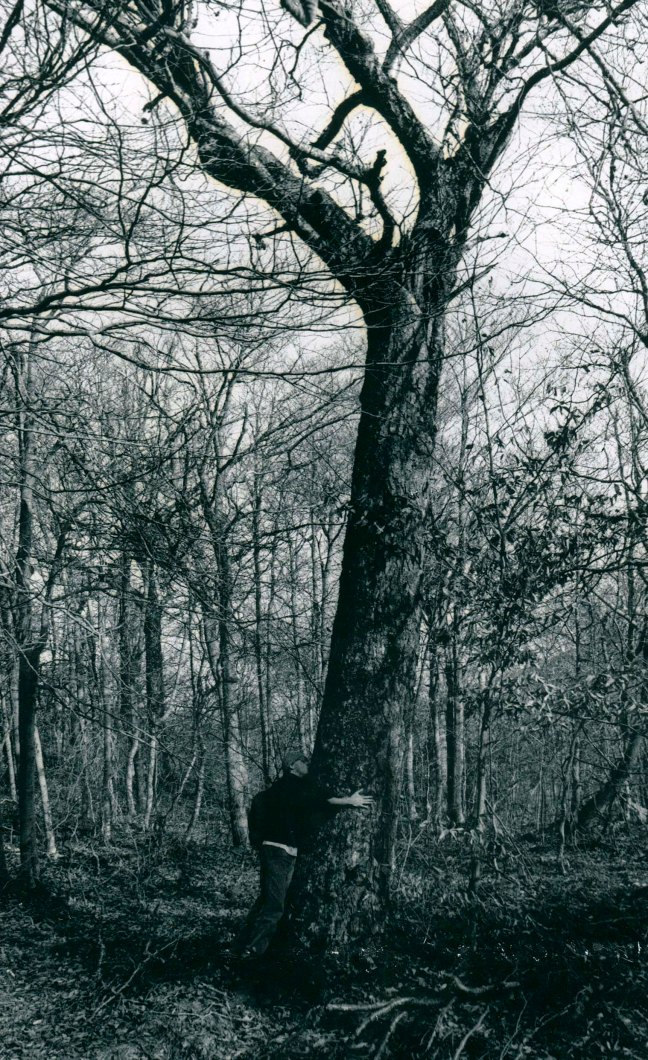

It’s a good time to go walking up to the naked knoll behind my house, the day bending toward 3 o’clock, several hours of work completed, but still an hour and a half before sunset. So a week into the new year, I leashed my dog Taiga and headed out up the snowpacked road, through a metal gate onto an unplowed Forest Service route, then a sharp turn up a snowshoe-trampled singletrack, winding between the darkening trees.

Melt clattered through clumps of chartreuse wolf lichen spackling the ponderosas, leaving rings of yellow in the snow below. The dog nosed the powder, noting the passage of every creature. She was eager to be out after a week confined to the house, recovering from a knee sprained in deep snow on this very trail. I settled into my breath, feeling my own housebound hours trickle out of my loosening bones and muscles, more animal now, finding my pace. The trail left the trees for a stretch, crossed a pure white slope where I paused to watch the mountains wrap away into the fog’s blanket, then ducked into a dark little draw and climbed the iciest stretch, 30 minutes in, near to the top now.

The phone buzzed and I fished it from my pocket—a text from a friend I hoped could dogsit during an upcoming reporting trip, something that couldn’t wait. Thumbing in my reply, I glanced up at Taiga, dragging me forward by the other arm. Her ears – little triangles of attention—aimed to the top like an arrow, suddenly swiveled towards something to my left.

I turned from the screen, then, let my hand fall. I registered a brown shape coming on. How near it was. Maybe 10 feet away. Seven. Silent. So silent. Moving with purpose. More…

I never meant for this to happen.

I never meant for this to happen.

This post

This post It was a bird of confluences. Nameless, to us. Gray as cloud belly, large as raptor, with eyes streaked over black as if with a stick of charcoal.

It was a bird of confluences. Nameless, to us. Gray as cloud belly, large as raptor, with eyes streaked over black as if with a stick of charcoal.